Early on New Year’s Day 2009, Oscar Grant was shot in the back and killed by BART police officer Johannes Mehserle in Oakland. Within days, the streets erupted in protests that would continue for over two years. A dramatization of Oscar’s final day was portrayed in the 2013 critically acclaimed film Fruitvale Station.

Most instances of police violence, however, are not as deeply ingrained in the public consciousness. Miguel Masso worked as a police officer in New York City in 2007 when he and fellow officers severely abused prisoner Rafael Santiago. Masso resigned rather than give an interview about the incident. Nevertheless, he found work with at least two other police departments. In 2012, Masso shot and killed Alan Blueford in Oakland.

Masso is far from the only repeat offender. Oakland police officer Hector Jimenez shot and killed an unarmed Andrew Moppin in 2007. The following summer, Jimenez went on to kill Jody Woodfox, also unarmed. OPD Sergeant Patrick Gonzales shot Ameir Rollins in 2006, causing him to become paralyzed, then killed Gary King Jr. in 2007.

Multiple instances of abuse or murder by the same officer are nearly impossible to follow with the systems available today. There does not exist a comprehensive database tracking police violence across California, much less the United States. The general public does not know in how many shootings, beatings, or assaults an officer has previously been involved.

This is a mistake. California must begin collating information on officer misconduct from across the state into a central database, accessible to the public, so we can better understand the nature of police violence in our state and prevent bad cops from moving freely between cities, their violent pasts hidden from residents.

The abuse is not confined to police shootings. In 2016, a police sexual abuse scandal involving an underage sex worker blew up in Oakland and eventually ensnared 30 law enforcement officers across the Bay Area. Discipline meted out was relatively minor. Internal investigators who covered up the misconduct were not held to account. Some were even promoted. District attorneys largely looked the other way, pursuing a few feeble cases.

It’s not uncommon for cops with dirty hands to be in positions of power. OPD’s Ed Poulson and others beat Jerry Amaro to death while in custody in 2000. Despite having instructed his subordinates to hide the cause of Amaro’s injuries, Poulson was later placed in charge of Internal Affairs, overseeing investigations into police misconduct.

This is but a handful of examples from a single city, Oakland, where various law enforcement agencies have been directly or indirectly responsible for the deaths of at least 198 people since 2000. In just the last five years, there have been 35 in-custody deaths at Alameda County’s Santa Rita Jail. Hundreds more have died after interacting with law enforcement in San Francisco, Vallejo, and Sacramento, in cities large and small across Northern California.

These accounts have barely touched on instances of non-deadly violence, civil rights violations, and other crimes committed by police, nor their related coverups, of which there are plenty. Taxpayers are on the hook for related lawsuit settlements.

Who can keep track of it all? Sadly, most of these incidents and the connections between them invariably slip down the memory hole while the officers remain on the force.

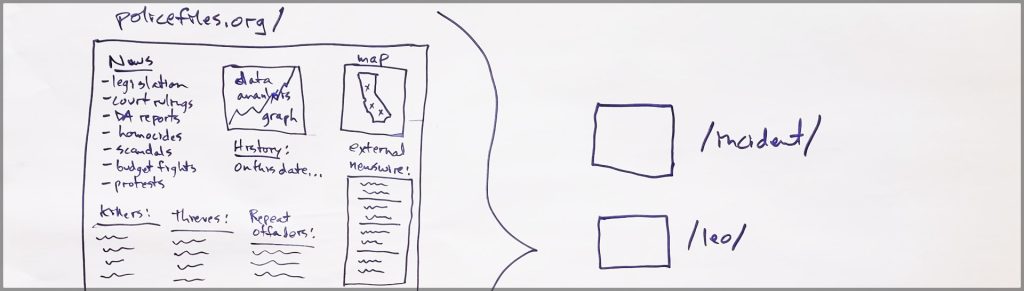

We need a centralized hub for information on law enforcement violence and corruption across Northern California. State, county, and local governments aren’t doing it. Police departments aren’t doing it. Solid non-profit models do exist in a few areas around the country which cover distinct aspects such as use of force or civilian complaints, as well as national ones tallying and mapping police killings, but there is no comprehensive resource for this region.

Since SB1421 went into effect this year in California — requiring law enforcement agencies to divulge information on the discharge of a firearms, use of force resulting in death or great bodily injury, and sustained findings of sexual assault or dishonesty — excellent journalistic exposés have revealed previously hidden misconduct. Still, without a centralized repository tying together all of the stories of individual officers and departments, journalists have to seek records from individual departments and stitch them together, a time-intensive task.

Ideally, a statewide database would compile police misconduct records from the streets to the jails, including documentation on the role district attorneys and city leaders play in fostering the current environment of police impunity. With an easily accessible database, anyone so inclined could create journalistic and infographic analyses to enhance our understanding of policing across our communities.

A public-facing website would feature pages for counties and cities which link to further information on detention facilities, law enforcement agencies, individual officers, oversight bodies, incidents of violence/corruption, and victims of police abuse. For ease of use, it should be searchable by criteria like city, agency, officer, victim, and year.

The database would be a valuable tool for journalists, civil rights attorneys, police accountability organizations, and the general public. It should humanize victims of police violence and include references to family support networks. The project should be built from ground up in collaboration with these stakeholders to assure it is as useful as possible.

It’s long past time California ensured its citizens understood the state’s track record of police violence. With SB 1421, we’ve taken a big step forward in undoing secrecy surrounding cases of misconduct. Now, let’s make these records as accessible as possible by hosting them in a central, easy-to-use database open to all.

David is a long-time independent journalist covering social justice and police accountability movements. He is fundraising to build a police accountability database for Northern California.

Originally published in the Sacramento Bee “California Forum” section on July 06, 2019.